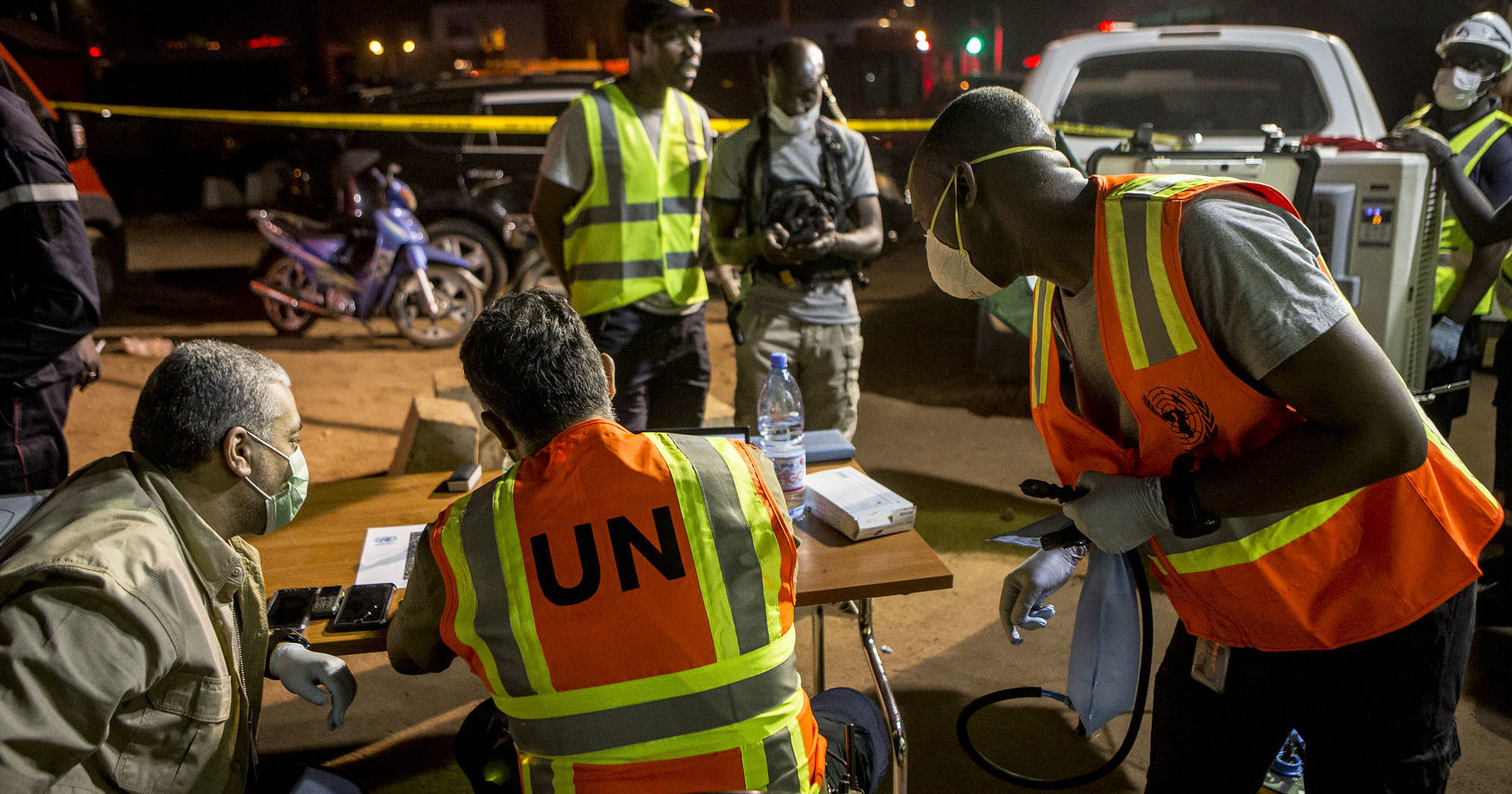

The U.N. mission in Mali coordinates the decontamination of a public market during the COVID-19 pandemic. | MINUSMA/Harandane Dicko

COVID-19 has introduced new challenges for development, exacerbated existing challenges and raised the risks of knock-on effects for the next three to five years. Healthcare systems have been stretched to their limit, social and economic inequalities have widened, mass unemployment has contributed to increased poverty and governments have struggled to deliver services amidst political unrest. In an increasingly connected world, the pandemic has shown us how collective action is required for complex challenges.

“Building back better” must be a shared imperative for fragile states and development partners alike. In the New Deal for Engagement in Fragile States, we have the principles to partner for better aid delivery in the most challenging contexts. Yet we still have a disconnect between knowing right and doing right on the ground in fragile states, where it matters most. Are we missing something to change our behavior – do we need a Greta Thunberg of aid, do we need to change how we partner on the ground or do we need to change who does what to find local solutions? Or maybe all three? Or maybe something else? This year the New Deal turns ten years old and we still have time to use the agreement to reach the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and ensure no one is left behind. How can we ReNEW the Deal to do better in the coming decade, coming out of the COVID-19 pandemic?

The World Bank’s Strategy for Fragility, Conflict and Violence simultaneously cites the Bank’s (and the world’s) development goal of eradicating poverty by 2030 (SDG 1.1) and the projection that more than 60 percent of the world’s extreme poor will be concentrated in fragile states in 2030 – a more dire prediction than just five years ago. Both can’t be true! We can’t eradicate extreme poverty and still have millions of people living in extreme poverty concentrated in fragile states. And poverty is not unique, very few fragile and conflict-affected countries are on track to achieve very few SDG targets. While some countries have emerged from conflict and are showing signs of escaping fragility – such as Colombia, Liberia, Nepal, Rwanda, Timor-Leste and the Solomon Islands – many others remain trapped. How do we reconcile our ambitious development goals with the knowledge that reform, resilience and development will take a decade or more?

We’ve heard all this before. Coming out of the financial crisis of 2008, we had agreements from Accra, Paris and Busan to keep us moving forward. In November 2011 the New Deal for Engagement in Fragile States was signed by more than 40 countries and multilateral organizations at the Fourth High Level Forum on Aid Effectiveness in Busan, South Korea. The landmark document iterated a new commitment by development partners to support nationally owned and led development plans for greater aid effectiveness in fragile and conflict-affected states.

When the New Deal was new, we didn’t have to take into account social distancing or vaccinations, but the problems we were facing then persist today and the solutions proposed at the Busan Forum still work. The New Deal’s key tenants call for donors to coalesce around country owned development strategies and to support and build capacity in local institutions to lay the groundwork for sustainable peace and development. But in too many cases, we’ve yet to turn these principles into sustainable development with traction in these most difficult environments – we face an implementation gap between knowing and doing. We keep repeating the same mistakes, so what can rattle our cages and get us out of these traps?

We’re hosting a conversation about this topic at next week’s Stockholm Forum on Peace and Development and reached out to our networks to find a Greta Thunberg of aid – someone knowledgeable about how aid and development work, what is needed in fragile states and can speak plainly to donors and representatives of developing countries about what their future looks like and what they need from us to build it. We found some exciting speakers and we’re looking forward to the conversation, but everyone we asked said they couldn’t think of a Greta (despite all of our collective efforts to promote young voices in development). Without someone to look back from the future and tell us how we’re failing them, we create no demand for doing better today and our implementation gap continues to grow. Do we need a Greta to keep us honest?

The Institute for State Effectiveness’ (ISE) Re-examining the Terms of Aid (RTOA) was motivated by the underlying challenges of explaining why this implementation gap persists.

RTOA posits that the implementation gap is largely a reflection of the failure to address the incentives that drive behavior and outcomes. Put differently, the implementation gap reflects the tendency to focus on the symptoms of poor development practice rather than its underlying drivers. Symptoms often include the fragmentation of development assistance, the substitution of state functions by external actors and development partners’ failure to contextualize their programming. However, these symptoms are the results of development delivery shortcomings that occur when principles, knowledge and lessons are not put into practice.

Amidst the urgency of the current state of affairs, the need to address the implementation gap has reached a critical point. Drawing upon the experience of ISE and other partners in fragile state development assistance, here are some of the key issues that have been put forward – driven by underlying incentive structures that contribute to the implementation gap:

Focusing on these areas can shift the incentives and behaviors that are driving the implementation gap. If the incentives don’t shift, and national governments and donors are not real partners going forward, perhaps we need to think about new engagement models. Does the principle of ownership always mean national government? Do donors always have to sign the checks? Pooled funds, joint delivery platforms, Give Directly, the Grameen Bank and community driven development are all examples of success that avoid traditional donor-recipient relationships and the pitfalls listed above. Maybe partnership in the 21st century just looks different than the system built in the shadow of the Marshall Plan?

The global consensus on development practice, and in particular on principles of local ownership, have always assumed that engagement occurs at the country level. But maybe we should challenge this. After all, we know that many crises occur at the regional level. And even if they are primarily confined within a country’s borders, the implications and knock-on effects for the region are significant. Politics, similarly, both influence and are influenced by the politics of neighboring countries. Naturally then, peacebuilding and development efforts should also have a corresponding regional dimension.

China’s Belt and Road Initiative, the emergence of new, active donors like Turkey and the Islamic Development Bank, the necessity of working at the triple nexus (humanitarian, development and peacebuilding, different in every region) and the growth of regional organizations that can negotiate regional solutions like the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) and the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD) speak to the demand side of reform of the international system that transcends our old models.

The time to ask ourselves these questions is now. For the past decade, we have agreed on the goal of development in fragile states – to help forge pathways out of fragility towards self-reliance. But for far too long have we agreed on the principles on how to get there, without results. We need a different way. Unfortunately, time is running out if we’re to deliver on our 2030 agenda. Recent publications, including the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s States of Fragility 2020 and the United States Institute of Peace’s Addressing Fragility in a Global Pandemic, have hinted at these questions by raising the need for new approaches. The passing of the Global Fragility Act in 2019 and a new U.S. administration provide new opportunities. Let’s turn our attention to radically new ways of thinking to support a new generation of reformers and to ReNEW the Deal.