By Pat Austria Ramsey, ISE Data & Digital Lead

In times of crisis, the imperative of leadership and prioritization is more prominent than ever before. Today, as the impacts of COVID-19 are felt by all countries, the salience of good governance becomes universal and we must revisit what it means for a state to function effectively. How do leaders lead in crisis? With so many competing imperatives, how do we prioritize? What lessons can we learn from countries that have faced crises, and set out on a sound recovery path, in the past? How can we more effectively use data to scale what works?

Amidst the COVID-19 crisis, many leaders have relied on data to drive decision-making and the experience of others. These insights are used to model both the immediate response and the broader reforms needed to offset the long-term impacts of the shock. The ongoing pandemic and reverberating second-order effects highlight the importance of understanding a diverse set of recovery pathways and indicators. Tools such as ISE’s Reform Sequencing Tracker provide a way to quickly understand the menu of options available and the different sequences adopted in different contexts after crises.

In 2018, ISE’s Data and Digital Team began the Reform Sequencing Project to better understand how leaders decide and prioritize reforms in times of crisis. The starting point was that there is no single roadmap for success – it is well established that different countries have followed different pathways. The goal was to codify the widest array of reform pathways possible – providing depth, detail and analytical capacity to information that typically sits in static PDFs in Ministries of Planning.

To date, ISE’s Reform Sequencing Tracker includes over 24,000 reforms that have been coded in over 25 countries. It documents the stories of the countries in every region in the world, spanning decades of history and reform leadership in a range of crises – conflict, natural disaster, pandemic, financial crisis and political transition. In doing so, the tracker aims to challenge the traditional lessons learned model where the focus is placed on the deemed successes and failures. In understanding that each crisis environment and reform agenda is unique, the database provides decision-makers with the information and tools that they need to understand and learn from a wide menu of reform pathways.

What does this mean in practice? The Reform Sequencing Tracker has three main outputs:

The foundational premises of the Reform Sequencing Tracker have only been affirmed by the needs brought on during the COVID-19 pandemic. Many leaders have relied on data and the paths of others to model their responses. The unprecedented nature of the crisis drove greater demand for the rapid transference of information and data-driven decision making. Interesting as well, governments were not just interested in what the United States or Europe were doing. Though often seen as the guideposts for many policy decisions, the United States, Europe, Singapore and South Korea provided just one story out of many. Understanding that their capacity and needs might vary, governments were just as interested in what New Zealand, Uruguay and Hong Kong were doing in the crisis.

“Everything you planned and promised to ordinary people, when a crisis hits, you must change your plan.”

– Boris Tadic, Club de Madrid member, former president of Serbia

Leaders are always tasked with making difficult decisions on prioritization and sequencing. In crisis environments, the need for expediency and effectiveness becomes exponentially greater.[1] Whether in government, development or the private sector, leaders begin their tenure with visions of their country or organization’s future. In a crisis environment, leaders are forced to reconsider these priorities to respond to the new issues at hand. Providing leaders with a wide array of reform stories can illuminate pathways that were once unrecognized and help balance the short-term demands of the crisis with the longer-term visions of development and transformation.

“It is easy to feel overwhelmed – 70 percent of the time leaders are in reactive mode, and it is difficult to get out of it.

- It is important to balance time frames – look at 1-2 months, but also consider the medium- and long-term needs

- Citizens need to see something, but a lot of the important things are not visible – budgets, supply chains, etc. – leaders must find a balance

- There needs to be more focus on prioritization and sequencing. You cannot do 1,000 things – what are the 3-5 things you can do first?

- Social inclusion is an imperative – how does a leader take time to listen to citizens? In fragile states, which are almost all youth majority countries, how do you incorporate the voices of vulnerable people?”

– Clare Lockhart, director of the Institute for State Effectiveness

The proliferation of data no longer binds the development community to the anecdotal experience of experts or popular case studies. We can, in a systematic yet detailed manner, lift stories from various crisis environments to help build reform pathways that are distinct and evidence-based. In addition, understanding that their reforms have a place in a broader sequence and trajectory of development can help decision-makers prioritize during difficult times.

“All systems – local to international – face levels of fragility, even more important during COVID-19. It is crucial to learn and revise how they respond to crises.”

– Amat Alsoswa, former minister of human rights in Yemen

The spectrum of fragility and governance issues manifests itself in the varied experience of citizens. Leaders must recognize the unique challenges communities face and be empathetic to the political and social culture. Often, decision-makers can look to the most developed nations to provide examples of the road forward. While appropriate in ambition, these examples do not consider the unique starting points each country and community face.

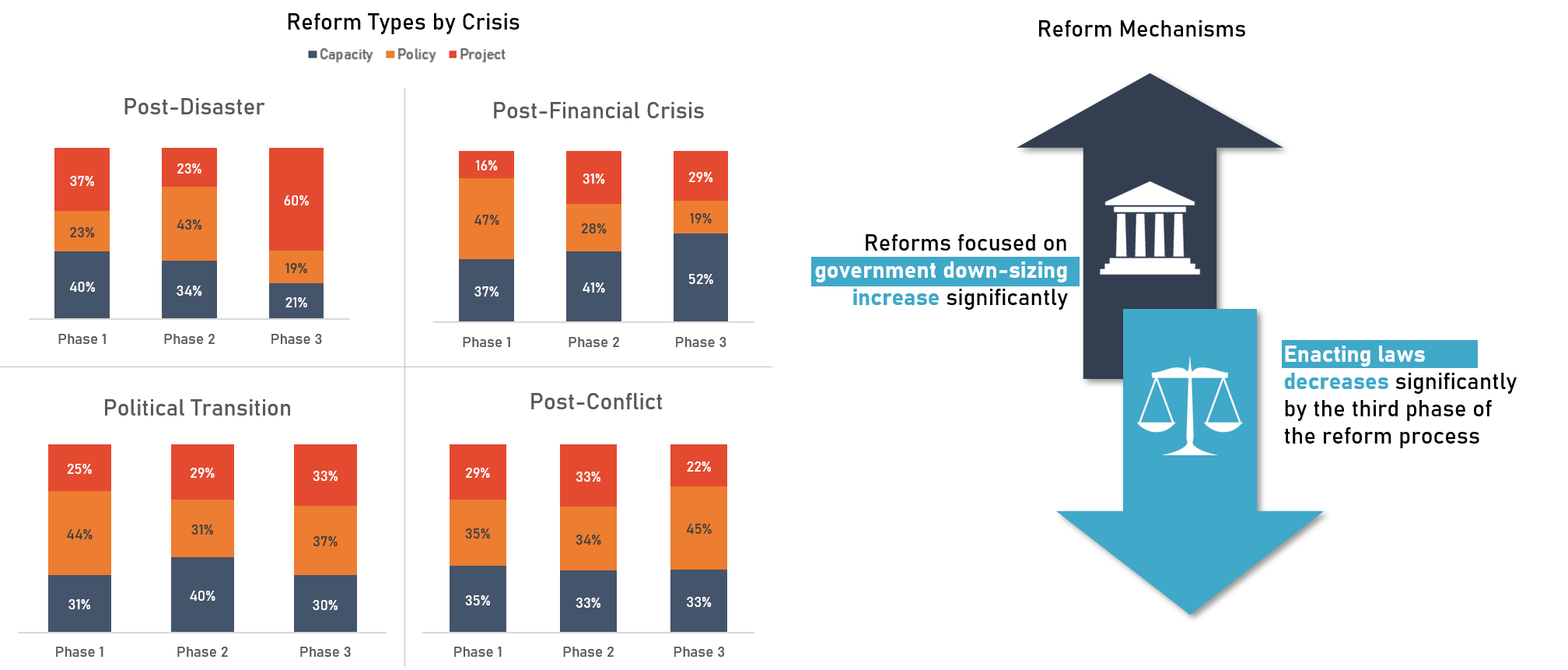

Preliminary analysis from the Reform Sequencing Tracker shows several interesting trends. Reform types and mechanisms vary greatly depending on the type of crisis (I.e. the shock that triggered the need for reform), The tracker classifies actions as three main types of reforms: capacity, policy or project.

We see some governments in crisis situations favoring more policy-based reforms while others favor more capacity-based measures. In addition, how governments use various mechanisms – government downsizing, the passing of laws, changing operational procedures, etc.—can have a significant impact on the reform pathway.

How capacity, project and policy reforms are distributed across the three phases of different crises.

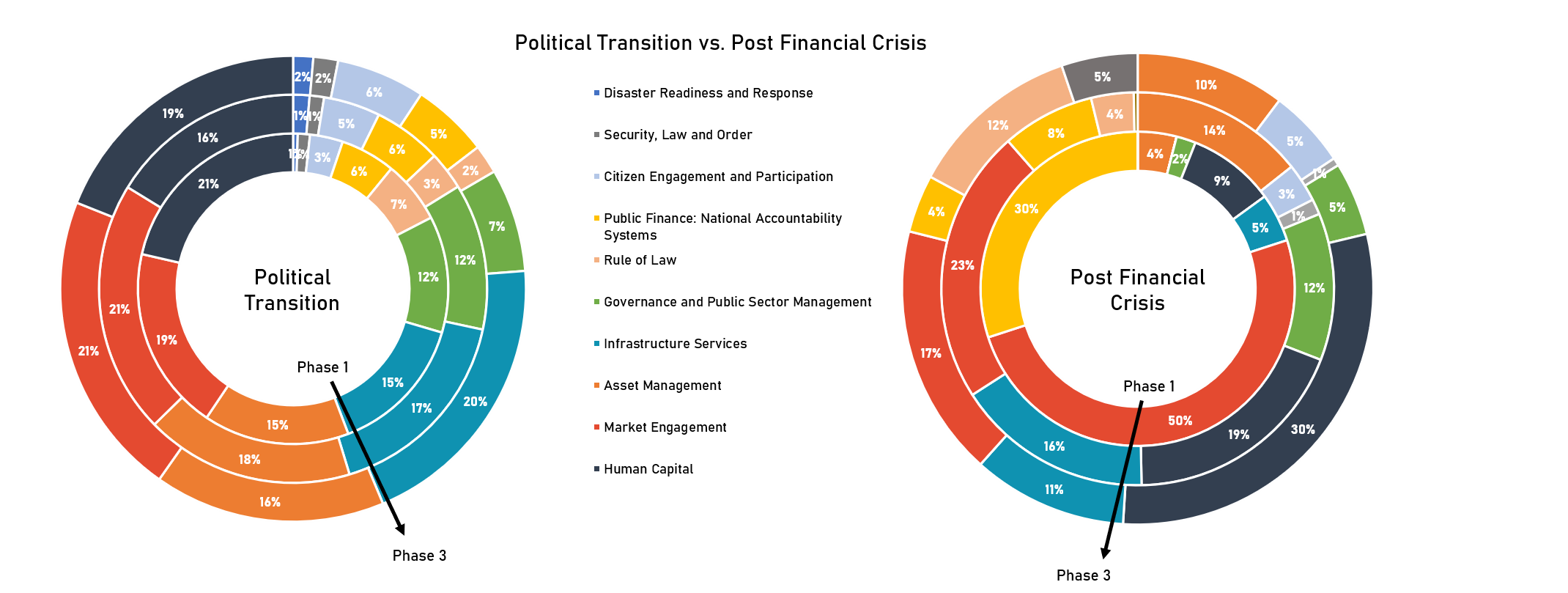

Countries facing political transition typically adopt a more diverse set of reforms compared to countries facing a financial crisis. In a financial crisis, leaders typically begin, unsurprisingly, with reforms focused on market engagement and public financial management. Interestingly, by the final phase of the reform agenda, countries in a financial crisis dedicate 30 percent of reforms to human capital (growing from just nine percent in the first phase). Put this in contrast with countries in political transition, where reforms remain varied at every phase of the reform process and human capital only constitutes 19 percent of reforms even in the final phase.

Comparing political transition and post-financial crisis reform actions categorized by the function of the state.

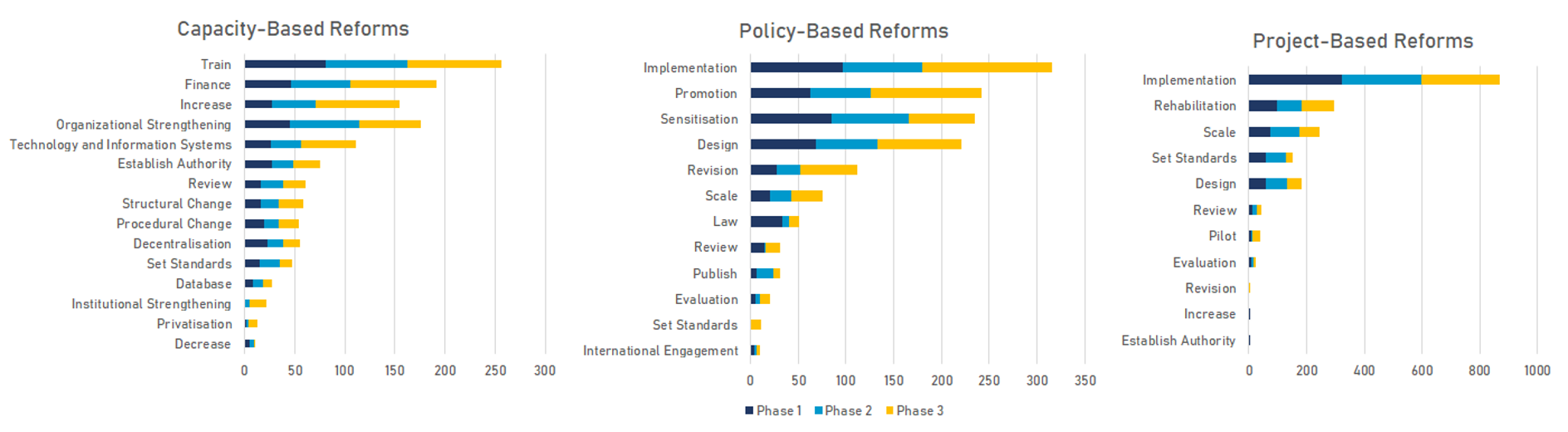

In virtually all crisis environments, governments endeavor to improve the human capital system. Human capital is a complex and multi-disciplinary field that rests on improved education, employment opportunities and social protection mechanisms. Similarly, human capital reforms can be enacted through different types and mechanisms. Between Phase 1 and Phase 3, we see that capacity-based reforms increase while project-based reforms decrease over time. Looking specifically at reform mechanisms, most capacity-based human capital reforms focus on training the civil service while policy-based reforms focus on implementation and promotion. Project-based reforms are largely implementation and rehabilitation.

Actions within the three different reform types.

The Reform Sequencing Tracker allows users to search through human capital reforms based on several different tags – type, mechanism, region, country, economic status, crisis type, etc. – to draw the parallels that are best suited for their country and context. Perhaps a country knows that its system currently lacks the policy foundations needed to support human capital reform. Through the Reform Sequencing Tracker, users can search specifically for policy-based reforms in any number of human capital priority areas, whether that be employment generation, curriculum improvement or social protection.

Beyond providing trend analysis, the Reform Sequencing Tracker aims to provide researchers and decision-makers with a library of reform actions to provide a detailed and nuanced menu of options. Leaders typically become overwhelmed by the barrage of priorities and are forced to rely on anecdotal experience. The Reform Sequencing Tracker can provide leaders with both an overview of the varied roadmaps countries have taken, as well as the specific reform actions that formed the basis of their vision.

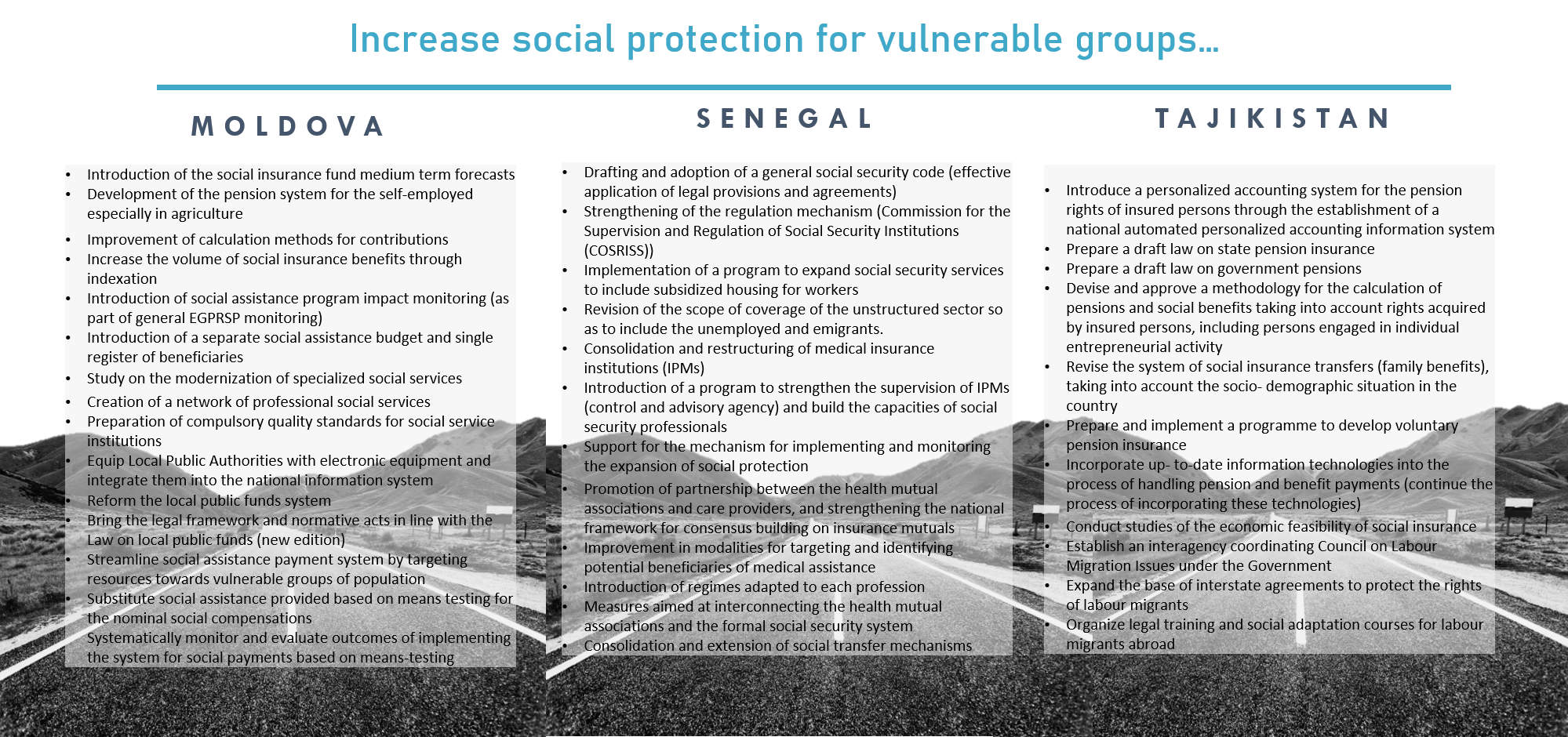

Social protection reforms across Moldova, Senegal and Tajikistan.

Data does not absolve leaders from the decision-making process – but it can strengthen its legitimacy and effectiveness. The demands of a crisis situation force many governments to proceed with the information and traditional methods they have become accustomed to. In turn, the approach of international development can, at times, seem anecdotal. The COVID-19 pandemic has changed the world in an unprecedented way and forced us to reconsider the traditional model of development.

All countries now face unique challenges brought on by the same critical shocks of the global pandemic and reverberating financial and social crises. As we look towards the future and the other challenges ahead of us, we see the need for the continued transference of information – information that is inclusive and detailed. That is what we hope to do with the Reform Sequencing Tracker. The Reform Sequencing tracker aims to be a valuable tool to democratize reform information and provide researchers and decision-makers with diverse, actionable and relevant data.

We hope you will explore the beta version of the Reform Sequencing Tracker. Since our launch in August 2020, we have presented the Reform Sequencing Tracker at the World Bank Fragility Forum and United Nations World Data Forum and have received highly positive feedback. However, we know we still have plenty ahead of us. In the coming months, ISE hopes to establish a performance component to look not only at “planned reforms” but evaluate whether they were completed and successful in their aims. Did countries that dedicated more reforms to human capital actually see improvements in human development indicators? Do certain types of reforms perform better in particular crisis scenarios? Does the timeline of the national vision actually matter?

This phase of work, like the one before it, will take a tremendous effort. We know there is no silver bullet to reforms. The COVID-19 crisis, like every crisis before it and every crisis after it, will have a number of different outcome permutations. However, by creating datasets that are more diverse, inclusive and data-rich, we hope that we can gain a better understanding of what different reform pathways can look like.

[1] On June 9, ISE partnered with the World Leadership Alliance-Club de Madrid to open the World Bank’s virtual Fragility Forum to answer questions and discuss how leaders and development institutions can prioritize reforms in these unique crisis situations. Moderated by Raj Kumar, the President of Devex, the panel featured President Boris Tadic, former president of Serbia; Minister Amat Alsoswa, former minister of Human Rights in Yemen; Franck Bousquet, senior director, Fragility, Conflict and Violence at the World Bank; and Clare Lockhart, director of the Institute for State Effectiveness.